IMPOSTER PHENOMENON IN MARTIAL ARTS

Dr Romany McGuffog December 2020

Imposter Phenomenon in Martial Arts

Preamble

This essay is in an unusual format. It will be a combination of discussing research, my own experiences, and exploring the experiences of others through a survey. I would also like to be clear that this essay is not an attack on the martial arts industry. This essay is an exploration of an issue that is prominent in many areas of life, with a focus on how this issue works in a martial arts context. Ultimately, I will be critiquing martial arts but also providing potential solutions that are either already in place or could be implemented.

Personal Background

First, it is important to understand my background and context to explain where I am coming from in this essay. My karate journey began on Wednesday, February 1st, 2006. I was 12 years old and had never really committed to any sports long-term. I had tried tap dancing (which lasted for about a month) and swimming (which lasted for a couple of years but I quit once they suggested that I do squad training and commit to more than just learning how to swim). On the other hand, academia came much more naturally to me. I have a vivid memory of being asked to swim six laps of the 25-metre pool and almost passing out halfway. I was always happy to have a go in sports at school, but I actively avoided any fitness sessions (like the beep test). I grew up with my dad constantly telling stories about his childhood experience of taekwondo. I always wanted to give martial arts a go but doubted my physical capabilities.

When I finally started karate, I was hopeful that I had finally found a sport that I could stick with, but I was doubtful that I would be any good at it. In the early days there were numerous highs and lows. I got complimented on my first day for how quickly I was picking things up. But I struggled immensely whenever we had to do fitness. I got an A on my kata

(back in the day when we were pretested using grades) and I remember feeling like I was in dream. Surely there was no way that I was actually good enough to go up a rank? When I was a 9th kyu, I watched a green belt demonstrate Renhosandan and went home in tears because I did not think I would ever be able to remember so many forms, let alone do them well.

Once I got to yellow belt, I moved into the Intermediates and Advanced class, which was exciting but so much harder. For a few years, I trained in both the dragons and the adults class – too scared to permanently move away from the safety of the younger class. I finally committed to staying in the adults class once I had my brown belt. However, this meant that my first adults grading was for first kyu (and back then, we had to do everything from white belt up to your rank). I felt so nervous that I could not stop shaking before the grading. I was absolutely convinced that the only reason I had made it thus far was because amongst the other young people, my martial arts looked okay. But now that I was being compared to other adults, I was sure that Kyoshi would take one look at me and be horrified.

I was happy to stay on my first kyu once I received that rank. However, I was teaching classes on my own, and had been a first kyu for nearly two years, so Kyoshi was pushing me to go for the grading. Overall, I did really well at the pre-grading – I only got a handful of criticisms. However, on the day of the actual grading, I called my mentor Erin Hill in tears saying that I wasn’t ready and that there is no way that I could possibly go for black belt. In my mind, a Black Belt was incredibly fit, athletic, and flexible – which was certainly not how I would describe myself. I thought that even if I managed to get my black belt, it would probably be because they felt bad for me. But, I did get through the grading – it was the toughest experience of my life. Remembering all the kata and bunkai was the easy part for me – my fear for the entire day was “would I be fit enough to get through the day?” I was not just worried about the kumite (although that was obviously a big factor) – I was stressed about even being able to get through basics at the start. My fitness had improved since

starting karate but I would not describe myself as necessarily “fit”. And even though I passed the grading, it only took a few months for the glow to wear off and for the doubts about my abilities to creep back in.

It took me months to even train in a Black Belt class. I was terrified of the expectations within the class, and I didn’t think that I would fit in at all. When I finally did attend a class, I loved it, but it opened up more avenues of doubt. For example, going for Nidan and Sandan were really challenging experiences for me. When I went for Nidan there were not many other Nidans at that time. In my mind, the current Nidans were significantly stronger, fitter, more athletic, and more knowledgeable than I was. Even when I achieved my Nidan, I felt immense pressure that I would not live up to the expectations that come along with that rank. Thankfully, I graded with two other people and they were incredibly supportive. However, when I went for Sandan, the pressure was much worse. I was the only one grading for that rank at that time, and there were even less people to compare myself to on that rank. I felt that if I got my Sandan, I would be devaluing the rank for the other people who were actually real Sandans. Even now, going for Yondan, there are only a handful of people on that rank currently. Even though I know deep down that I am a good martial artist, there are abilities that I think a fourth dan should have that I do not. I question my level of fitness, flexibility, and athleticism, based on comparisons to other people on that rank or higher.

Furthermore, COVID-19 has had a massive impact on my martial arts training.

During the months of March, April, and June, we were sent into lockdown, meaning that the dojo was shut down. My work as a mental health researcher was also moved to working from home for a short period as well. I went from working all day at work, spending most of my evenings and Saturday mornings at karate, and squeezing in socializing wherever I could, to nothing. It was daunting at first. After finishing my PhD in August 2019, one of the hardest

things for me was adjusting to having free time again. I always had a pretty full schedule anyway, but when doing a PhD, you often feel like every minute should be spent doing something. And that meant I felt guilty whenever I had free time that I wasn’t doing something productive. So even adjusting to post-PhD life was challenging. But, to suddenly go into lockdown, where there was A LOT of free time, was terrifying. Thankfully, not long after the lockdown began, we had online karate training through zoom, which was incredible. However, it was still a massive reduction in time at karate for me. Normally, I would train for a couple of hours on Monday, Tuesday, and Friday, as well as an extra training session on Thursday mornings, and teaching on Saturdays. That dropped to an hour and a half of training on Mondays and Fridays. That was where the anxious feelings kicked in. I felt that the only reason I was okay at karate over the years was because I trained so often. With the reduction in training opportunities, I was really anxious that I would go backwards in my martial arts journey.

One of the first things I did with my spare time, was to focus on my exercise (my coping strategy has always been routine and distracting myself by staying busy). I started running laps up and down my driveway, I practiced karate and kobudo out the front of my house, and I started investing more time in flexibility training. This experience was a double- edged sword. For the first time in my life, I was being proactive and independent in my training (rather than relying on constantly going to classes so other people could motivate me to train), but it also highlighted my glaring flaws. By putting so much time and energy into exercising, I was hyper-focusing on wanting to be fitter, more flexible, and more athletic in general. I would also start to feel guilty if I had a single day where I did not get some exercise in. In my head, I kept hearing “Well, a real 4th dan would be doing all of this exercise, why can’t you?”

For me, these feelings are not restricted to the martial arts part of life. These doubts and uncertainties are also present in my research work, where I often feel that I am not as far ahead in my career or as capable as I should be. I even feel these feelings in my general life. For example, I am 27 as of writing this essay, but I do not feel like an “adult”. I think about where my parents were at my age and I often question my “adultness”. Another example is the fact that one of the areas that my PhD focused on was sleep and its importance. However, in my own life, I have serious issues with my own sleep. Again, this leads me to question my ability – how can I research sleep and preach to others about the importance of sleep, when I cannot fix my own sleep?

During my PhD, I learnt about imposter phenomenon and realized that a lot of the feelings I had experienced throughout my life were symptoms of this phenomenon.

Imposter Phenomenon and the Research

The idea of imposter phenomenon was first introduced by Clance and Imes (1978).

The researchers found that many academics (particularly women) reported feeling like imposters in their work. Imposter phenomenon is defined as:

“The internal experience of intellectual fraudulence in individuals who, despite objective evidence of success in the form of outstanding academic or professional achievements, have a persistent, secret belief that they do not deserve their status or position” (Sonnak & Towell, 2001, p. 864).

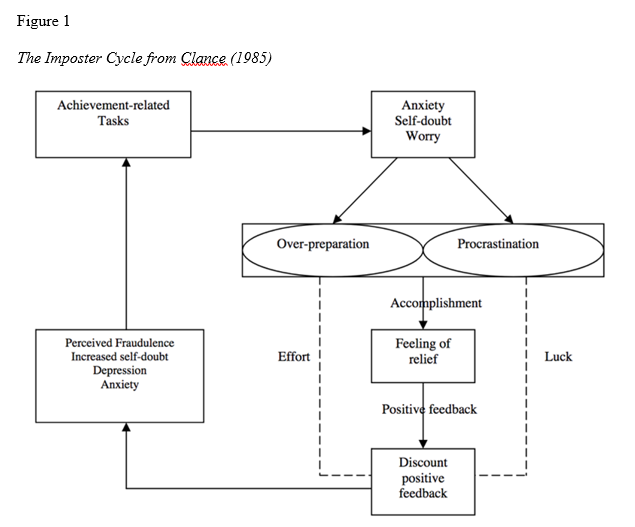

Clance (1985) identified six characteristics that can make up imposter phenomenon:

- The Imposter Cycle – This cycle begins with a task or goal which is anxiety- provoking. This anxiety then leads to either extreme over-preparation or procrastination and cramming. Once the task or goal is complete, there is an initial sense of relief or accomplishment, but the individual rejects or discounts

their success is due to their own ability. Either they believe their success is simply due to hard work (from the over-preparation) or luck (from the procrastination and cramming). This self-evaluation then leads to self-doubt about one’s abilities, which then starts the cycle again.

Figure 1:

- The need to be special or to be the very best – Clance observed that people with higher levels of imposter phenomenon are often top of their class/field/etc. which can become problematic when they enter somewhere that is full of other exceptional people. Thus, people can dismiss their own talents when they are not the very best.

3. Superman/Superwoman aspects – Similar to the previous characteristic, people experiencing imposter phenomenon can set unrealistic or perfectionist goals. When these impossible standards are not met, the individual is often left feeling overwhelmed, disappointed, and see themselves as a failure.Fear of failure – Consequently, people with higher levels of imposter phenomenon fear making mistakes or not performing to the highest standard, which leads to shame and humiliation. This fear is what often leads to over- preparation, to make sure that they cannot fail. Denial of competence and discounting praise – People with higher levels of imposter phenomenon attribute their success to external factors rather than internalising their success. They can also find reasons for why they do not deserve praise. This behaviour can often be misinterpreted as modesty or humility. Fear of guilt about success – People experiencing imposter phenomenon often feel guilty when their success is unusual from those around them because they fear being seen as different. They also fear that their success might lead to higher demands and greater expectations from others.

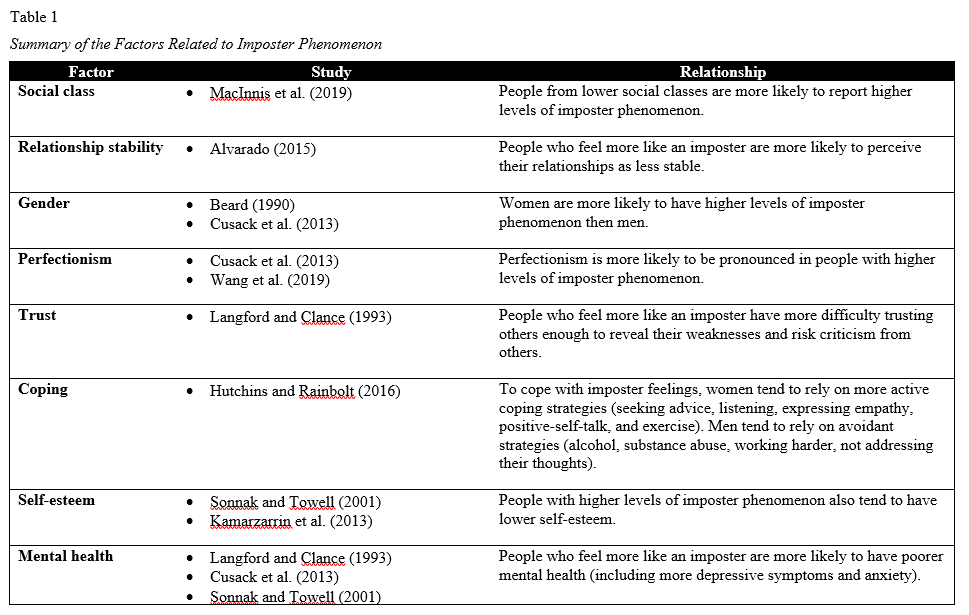

Looking through these characteristics, it is easy to see how someone might experience imposter feelings. Importantly, Clance (1985) believed that imposter phenomenon was not a pathological disease, but rather, that it interferes with an individual’s wellbeing. Meaning that, experiencing feelings of imposter phenomenon can be normal. However, if these feelings get to intense, or happen often, they can negatively impact wellbeing (Cusack et al., 2013). Furthermore, there are a number of factors that relate to imposter phenomenon (see Table 1).

9

Table 1:

Imposter Phenomenon and Martial Arts

Most of the research on imposter phenomenon focuses on experiences within academia. However, many of the ideas, symptoms, and solutions can be applied to a martial arts context.

For example, I can easily see how the six characteristics of imposter phenomenon relate to my martial arts experience. I certainly follow the Imposter Cycle, particularly in regards to over-preparation. And this often results in me discounting my ability because I feel that the only reason I did well at something is because I over-worked myself (i.e., the moment I stop, I will lose all of my ability and be back at square one). As a higher rank in karate, I often feel pressure (from myself more than anything/anyone else) to be the best and live up to the expectations of my rank.

Some research suggests that an academic is constantly looking at the people ahead of them (i.e., people with more publications, etc.) and these comparisons foster self-doubt (e.g., Bothello & Roulet, 2018; Jaremka et al., 2020). The problem is that despite outward appearances, the journeys that people take in academia can vary dramatically, and there is no one true pathway. Martial arts is very much the same. Often we can get caught up comparing ourselves to people who are higher ranks and get overwhelmed with self-doubt despite the fact that our journeys might be very different. For example, every time Sakamoto Sensei comes to visit Australia, I find myself getting frustrated that I can’t do the things he can and feeling like I will never get to his level. However, an outsider might point out that our martial arts journeys have been very different and that we are at completely different stages of our journeys.

Since everyone’s journey is different, comparison between students can be really problematic. Gardner and Holley (2011) highlight that imposter phenomenon can be experienced when one perceives themselves as different compared to the majority. For

example, I could compare myself to people who have made karate their career and get to spend every day working on it, or to people who train up to three hours a day, or people who have been training since they were old enough to walk. Realistically, I know that I might never be as flexible, fit, or athletic as some of these people. And that can be a very anxiety- provoking realisation.

Intense feelings of imposter phenomenon can lead to people (a) disengaging from their endeavours or goals, (b) avoiding evaluative situations, (c) having constant feelings of inadequacy, and (d) exhibiting an unhealthy pressure to succeed (Peteet et al., 2015). I often wonder if many of the students who leave martial arts, particularly at higher ranks, do so in part because of imposter feelings.

Survey on Imposter Syndrome in Martial Artists

As I started to become more aware of my own feelings of imposter phenomenon, I started to wonder if other martial artists felt this way. I had started looking into the research behind imposter phenomenon, and decided that a great way to explore this concept in martial arts, was to collect some data from other students about their experiences through an online survey. Please see Appendix A for a copy of the survey.

Methodology

I designed a 15-minute survey that included 40 individual items. An information statement was provided at the start of the survey which highlighted that everyone’s answers would be as anonymous as possible, and told participants that the purpose of the survey was to explore people’s martial arts journey. I specifically did not mention imposter phenomenon because I did not want to influence their responses to the questions about imposter phenomenon. I also provided the number to Lifeline in case any of the questions caused distress in participants.

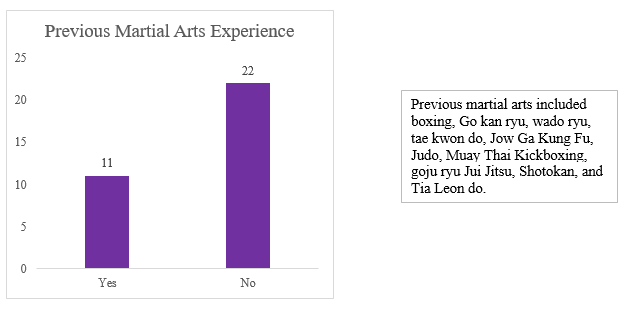

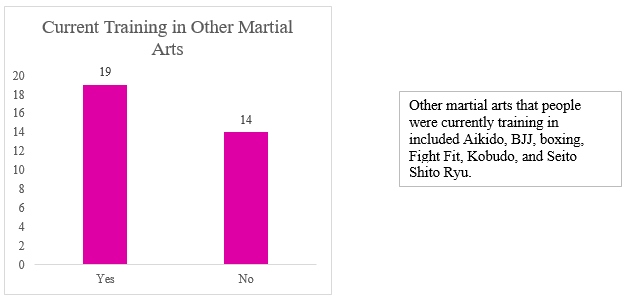

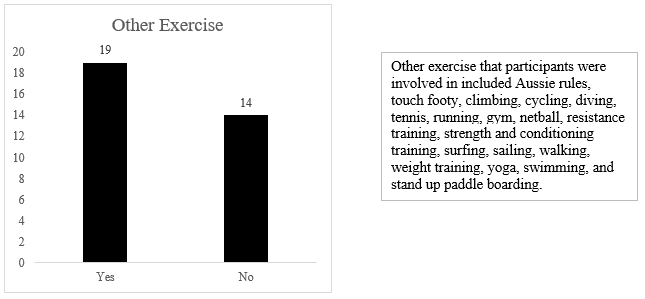

The first 10 questions asked about the demographics of the participants. These items included age, gender, belt rank, length of time on current belt, belt rank group, years training, previous martial arts experience, other current martial arts, other exercise, and number of training days. These items were all included because I wanted to explore if any of these variables impacted levels of imposter phenomenon. For example, do people who have trained for longer have higher levels of imposter phenomenon?

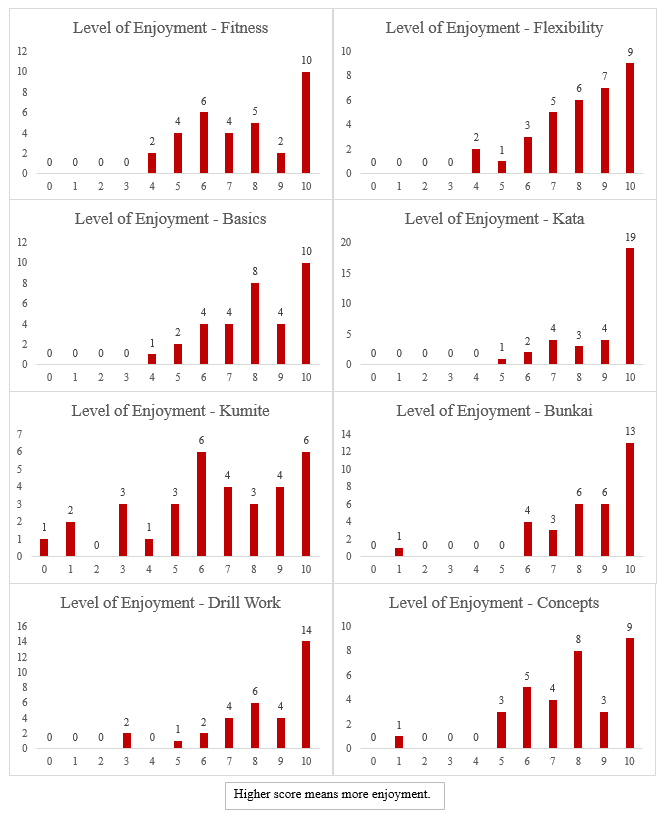

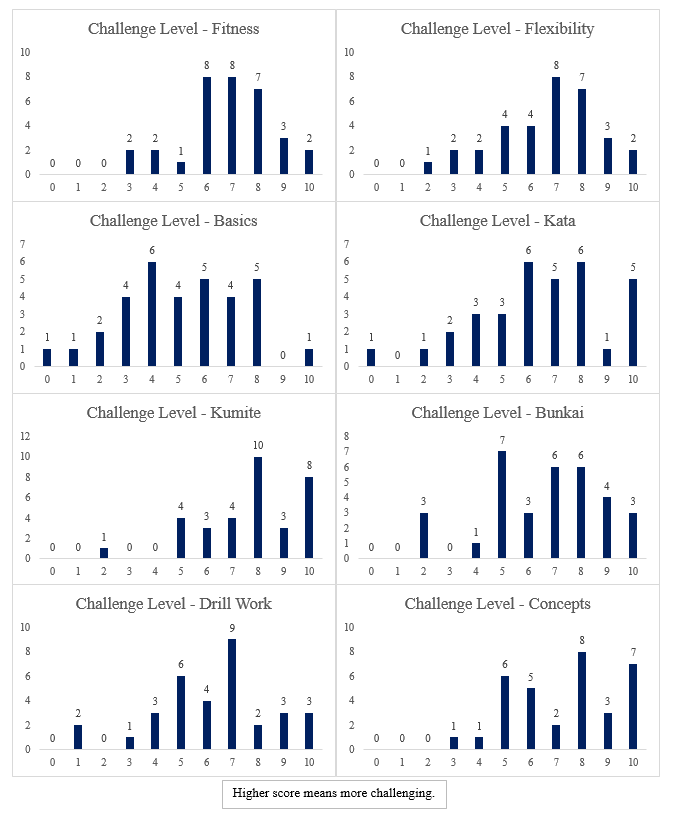

The next eight questions asked participants to rate their level of enjoyment of various martial arts activities, including fitness work, stretching and flexibility work, basics training, kata, kumite, bunkai, drill work, and conceptual drills. These questions were then followed by eight items about the same aspects of training, but instead asked participants to rate how challenging these activities were. The response scale ranged from 0 to 10, with 0 being not challenging at all and 10 being very challenging.

Following this section, I had nine questions about imposter phenomenon. Measuring imposter phenomenon is challenging, because there are many different measures available and there is not a “gold standard” measure yet (Mak et al., 2019). Each measure has its own benefits and problems. So, for my survey, I used a modified version of an 8-item scale provided by a researcher at the University of Newcastle, Dr Heather Douglas. Participants were specifically asked to think about their current karate journey when answering these questions. Some example items include “I sometimes shy away from challenges because of nagging self-doubt” and “I live in fear of being found out, discovered, or unmasked”. I added an additional question at the end of this section, “I also experience similar feelings as above in other areas of my life” to explore if participants only felt imposter phenomenon at karate. The response scale for these items ranged from not at all true (1) to very true (5).

I also wanted to ask participants directly about imposter phenomenon, so in the next section of the survey I provided a debrief statement which explained imposter phenomenon

and asked four questions. The items asked whether participants ever experience imposter phenomenon through their martial arts journey and how often, and how often they feel imposter phenomenon in other areas of their lives. There was also an open-ended question for participants to describe an example of imposter phenomenon that they had experienced.

The final item of the survey asked participants if they wanted their responses to be included in my research or not. Ordinarily, consent is implicitly given by doing the survey. However, I felt adding a consent item at the end was important since there was a level of deception involved in the survey, and I wanted to give participants a chance to withdraw their responses.

In total, I recruited data from 48 participants, however, only 33 completed the survey all the way to the end and answered the consent item. Thus, I only analysed the results from these 33 participants.

Results

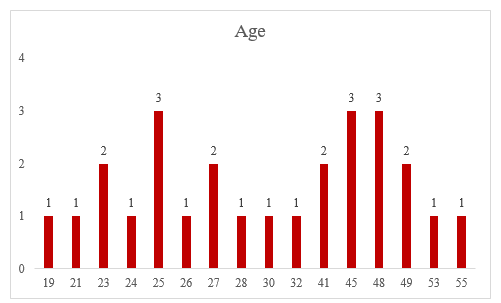

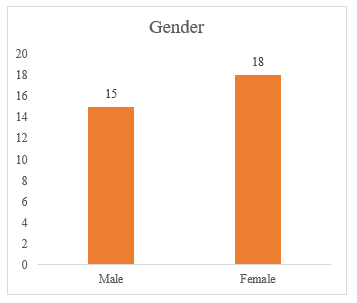

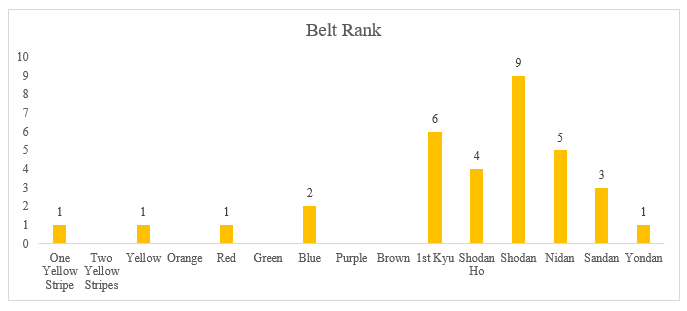

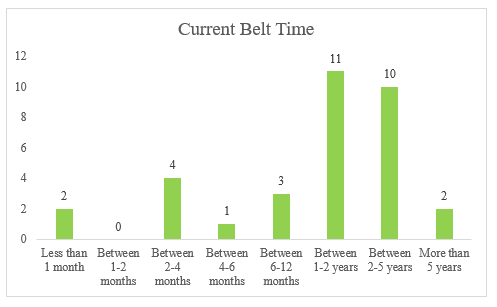

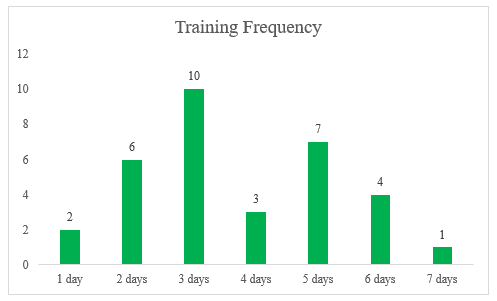

Frequencies and descriptive statistics. Despite the fact that I was only able to obtain a small sample size, I achieved a good spread of data across each variable. The age of the participants ranged from 19 to 55 (mean = 35.46, standard deviation = 11.73; seven missing age responses). The split for gender was fairly equal, with 15 males and 18 females. Please see Appendix B for graphs of each of the demographic items.

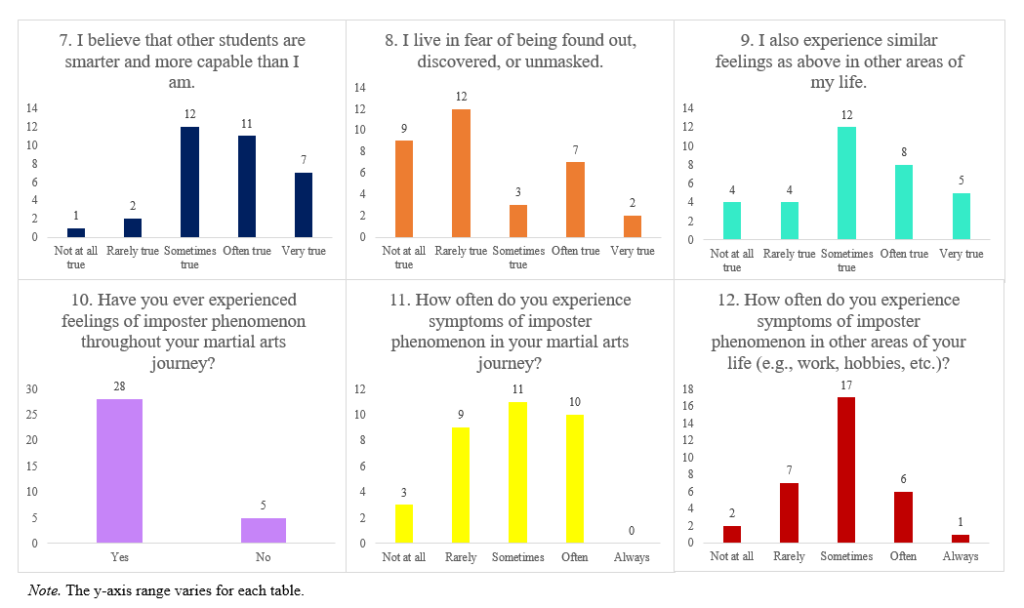

The first research question was to explore whether martial artists experience feelings of imposter phenomenon. As can be seen from the first eight tables below (see Figure 2), the number of participants who felt some level of imposter phenomenon varied across each item, meaning that most participants had experienced some imposter feelings in their martial arts journey. Note that these questions were asked before imposter phenomenon was explained to the participants. Interestingly, the question that asked “I hate making a mistake, being less than fully prepared, or not doing things perfectly” had no people report that it was not at all

true, and 25 participants (76%) said that they felt this sentiment was often true or very true. This higher level could be due to the fact that the term “mistake” is used a lot more in karate when talking about kata, etc. than it might be in academia. The ninth table shows that imposter feelings are experienced sometimes even in other areas of the life (meaning that karate might not be the only time they experience these feelings). When asked directly about whether they had experienced imposter feelings in martial arts, 28 participants (85%) said yes. Furthermore, 21 participants (64%) experienced these feelings sometimes or often.

However, no participants said they always experienced these feelings. Interestingly, the numbers in the ninth and twelfth table do not match up perfectly, despite the questions essentially asking the same thing. It could be that once participants were informed of imposter phenomenon they were able to more clearly articulate their experiences.

Figure 2:

Note. The y-axis range varies for each table.

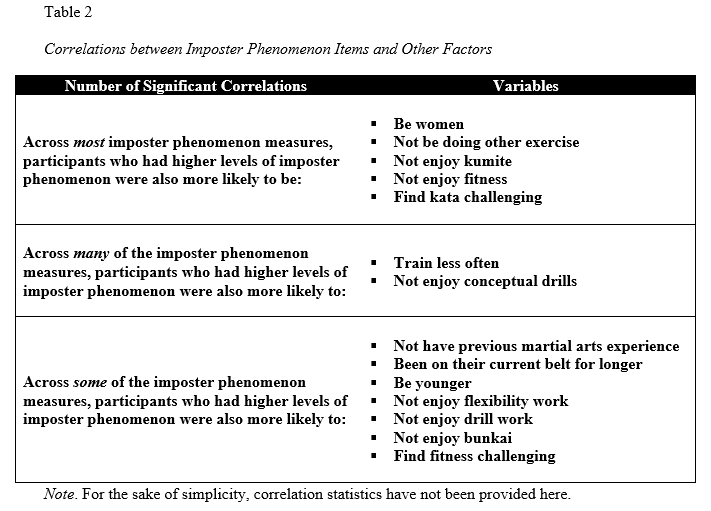

Relationships between imposter phenomenon and other factors. The second research question was to explore whether imposter syndrome was related to any of the demographic variables, enjoyment of karate activities, and the challenging nature of karate activities. There were a number of relations that were found (see Table 2). As can be seen from the table, the key variables that were related to nearly all of the imposter phenomenon variables included gender, participation in other exercise, enjoyment of kumite and fitness, and challenging nature of kata.

Table 2:

Note. For the sake of simplicity, correlation statistics have not been provided here.

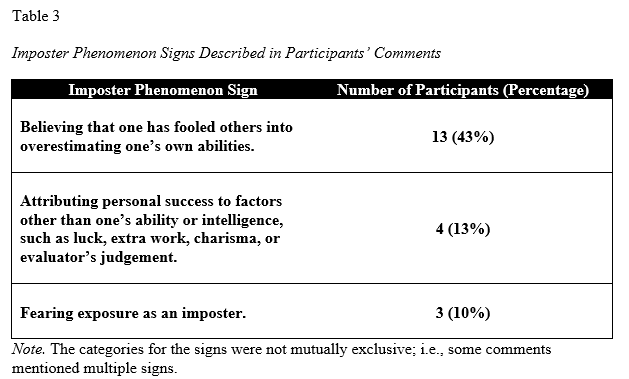

Comments from participants. In total, 30 participants provided comments when asked to describe an instance in their martial arts journey where they felt like an imposter.

Out of these comments, 11 (37%) people identified gradings as a situation where these feelings were present. A further eight (27%) participants highlighted that they felt imposter feelings when they were training (either in class or on their own). To break down the specific signs of imposter phenomenon, I followed the three key signs highlighted by Clark et al. (2014) and counted the number of participants that mentioned these signs in their comments (see Table 3). As can be seen from the table, the main imposter sign that people reported feeling was believing that they had fooled others into overestimating their ability. In martial arts, this can be a common experience where we feel like we do not deserve the rank we have.

Table 3:

Note. The categories for the signs were not mutually exclusive; i.e., some comments mentioned multiple signs.

Discussion

The point of the survey was to explore if other martial artists experienced feelings of imposter phenomenon and whether there were any factors that were related to imposter phenomenon.

Based on previous research (e.g., Beard, 1990; Cusack et al., 2013), it is not unexpected that women reported high levels of imposter feelings. However, the rest of the correlations are mixed, i.e., there are no clear and consistent factors (e.g., fitness). For me, this result could be due to the fact everyone has different ideas about what a good martial artist involves. That is, a person may feel that a key quality of a black belt is fitness, and so their imposter phenomenon relates to that. Alternatively, a person may see respect as a key quality, and so consequently feels no imposter feelings in relation to fitness.

It is critical to note that the survey was cross-sectional, meaning that we were only able to show correlation, not causation. This means that even though I found relationships between various factors and imposter phenomenon, I was not able to demonstrate the direction of the relationship. For example, even though I found that people with higher levels of imposter phenomenon were more likely to report not enjoying fitness, this result does not prove that not enjoying fitness leads to increased feelings of imposter phenomenon. It could be the other way around – having higher levels of imposter phenomenon leads to not enjoying fitness.

It is also important to note that I only had a sample of 33 martial artists. This means that the patterns that emerged in relation to imposter phenomenon may not be accurate or reflective of the wider population (i.e., all Chitokai students, or even more broadly, all martial artists).

Solutions to Reduce Imposter Phenomenon Feelings

There are two key approaches to reducing imposter phenomenon in general. First, we can take an individual approach – meaning that we can equip individual people with the skills required to better cope with any feelings of imposter phenomenon. This approach is common, with many researchers highlighting various ways to help the individual. The second approach

is to focus on the environment and culture to reduce any parts of these that may lead to feelings of imposter phenomenon. The reasoning behind this approach is that the emphasis is often on the individual rather than on the actual cause of the imposter feelings. Ultimately, we should be incorporating both approaches. People should learn how to process imposter phenomenon feelings and develop better coping mechanisms, however; if their environment or culture constantly imposes these imposter feelings onto people, then even with better coping strategies, they are fighting a losing battle. The main solutions are provided below, with connections to a martial arts context.

Talking to Others

One of the key solutions is to talk to others about your imposter feelings (e.g., Alvarado, 2015; Borhart, 2015; Clark et al., 2014; Jaremka et al., 2020; Lacey & Parlette- Stewart, 2017; Tiefenthaler, 2018). This idea is by far the most common solution provided in the research. The ultimate goal is that by talking to others about your imposter feelings, you will create connections with other people who may feel the same way you do, and provide a support network to help each other celebrate their successes. In more extreme cases, where imposter phenomenon is actually impacting an individual’s mental health and their day to day life, some researchers also recommended therapy – particularly group therapy (e.g., Clark et al., 2014; Jaremka et al., 2020; Joshi & Mangette, 2018). The journey of writing this essay and talking to others about it has highlighted to me how many other students (of various ages, experience, and ability) share the same imposter feelings. I am not sure if it has necessarily helped me personally, but it has helped me connect with different people.

Recording Positive Feedback

Another common recommendation is to make a record of the various positive feedback that you receive (e.g., Clark et al., 2014; Jaremka et al., 2020; Lacey & Parlette- Stewart, 2017; Mullangi & Jagsi, 2019; Sherman, 2013). By recording positive feedback, it

makes sure that the individual acknowledges the positive feedback rather than dismissing it. It also enables them to have something physical to remind them of their accomplishments. In my work as a researcher, I have tried to do this by printing out emails that people have sent praising my work. In karate, the way we do this is through the use of well-done cards and nominations for student-of-the-month. However, there are not many ways for Black Belts to receive acknowledgements of our successes (whatever they may be). Potentially, we could have discussions in Leadership or Black Belt class at the end of the year to talk to each other about our successes throughout the year. We could even do it at Black Belt gradings, as a way to finish off the grading. Another idea could be to have a monthly Facebook post/video about a Black Belt and what they have been working on, challenges, and goals.

Embrace the Diversity of Success

Some research has highlighted the importance of the different ways someone can be “successful” (e.g., Jaremka et al., 2020; Lacey & Parlette-Stewart, 2017). This solution is particularly relevant to a martial arts context because of the various pathways one can take on their martial arts journey. An individual could be aiming to win national competitions, or to gain their black belt, or simply to improve their physical ability. Within these different pathways, I think there are three common factors to address in order to embrace diversity: body shape, inclusivity, and gender.

Body shape. One of the key ways of embracing diversity of success is through the acceptance of various body shapes. For example, in our style, the types of black belts (and more broadly, the types of students generally) are all shapes and sizes. And importantly, people do not need to be a certain body shape to do well in martial arts. For example, bigger people can still be lightning fast and smaller people can be incredibly strong. But also, some people may never be flexible enough to do certain techniques, but this does not diminish their martial arts capability. Although martial arts are most certainly about community and

teamwork, ultimately, each person’s journey is unique and is entirely their own. The ultimate goal of martial arts is to push your body to its full capabilities and to build your character.

Thus, it does not matter what body you have, because it is about YOUR JOURNEY. In saying this, there are certainly some conformities that are required – one must do the techniques correctly and learn the various kata and bunkai. However, ultimately, it is about how to use your body to generate power. Therefore, I think that our style does a good job of being independent from body shape stereotyping for the most part.

Inclusivity. Martial arts promotes community and comradery with the people you train with, no matter their background (for example, religion, culture, values, etc.). A person’s martial arts ability is linked to their sporting background, for example, someone who has done dancing might understand hip motion better than other students. However, ability is also connected to life experiences such as work. Some people can explore martial arts through their own lens, such as a physics lens, a psychology lens, a spiritual lens, a self- defence lens, and so on. These different ways of experiencing martial arts is helps evolve the martial arts of those around us. One way we celebrate this type of diversity is through the essays we write for black belt gradings. These essays allow people to draw on their own experiences and knowledge outside of martial arts.

Gender. Finally, let us explore gender in martial arts. The topic of gender and martial arts is an essay in and of itself; so, for the sake of brevity, I will only discuss the connection to imposter phenomenon. First, martial arts can be incredibly empowering because gender can be disregarded in many activities. Martial arts is not necessarily seen as a sport for a particular gender in current times – indeed, we have a fairly even split of male and female students/instructors in our style. One of my favourite moments when training is having new students see me do something fairly simple (a higher level kata, or some kumite drills) and seeing the look on their face. Generally speaking, men see it as a break from stereotype

(especially if I demonstrate something that is all about power), and for women, it is empowering to see the physical capabilities of other women. This argument follows on from the above discussion about body shape – it doesn’t matter if women typically have different bodies to men, in a martial arts setting, these differences can be seen as advantages for different body shapes (agility, strength, height, etc.) or are not really seen as that different because of the fact that we are all just trying to generate power from our bodies. In these situations, I feel like I can overcome my imposter feelings.

However, there are times when I feel like an imposter because of my gender. For example, I have had a handful of male kyu-grade students who would refuse to hit me no matter what the drill. When I have confronted them about their behaviour, the answer I get is that they were taught never to hit a woman, and they are struggling to overcome that feeling. Although I completely understand that sentiment, I actually find that kind of statement quite problematic. The statement is a form of benevolent sexism where the person is not acting in a hostile way (e.g., women can’t do sports), but instead, trying to be helpful (Glick & Fiske, 1996). However, benevolent sexism stems from traditional stereotyping of women being weaker than men and needing protection. Fortunately, most students who have acted this way to me have learned to move past this as their training continued. I believe this is because we learn how to fight and work together in a controlled way, and we preach the message that we shouldn’t use our martial arts on anyone.

Furthermore, there are some activities in karate that do feel gendered (or at the very least designed for cisgender men), which then makes it obvious when a person does not fit. A common issue that I experience is having to adjust drills or techniques that require hitting my chest. In these situations, I often feel like the cisgender male is the default body type and it is up to me to work around that. Even further, one of our key self-defence moves is attacking the groin. Again, the assumption is that you would be hitting a cisgender male who would

find that very painful. In addition, sports karate still keeps men and women separate in the divisions. For me, this makes some sense for kumite where weight is important to consider. However, I do not believe that this is relevant for kata, and often leaves me feeling like I cannot compete against the men because I am a woman. I think it is also important to acknowledge the binary view of gender in sports karate which does not account for people of different genders. For me, allowing the chance for genders to mix is really helpful for reducing imposter feelings. For example, pairing students based on size rather than gender (as long as both parties are comfortable), having instructors demonstrate activities with different genders, and creating mixed tournament events for adults.

Improving Leadership

Finally, there was some research that suggested the important role that leaders can play (e.g., Clark et al., 2014; Jaremka et al., 2020). First, supervisors and other leaders should be made aware of imposter phenomenon and any staff or students that might be feeling that way. This enables a healthy dialogue to help people discuss their feelings. Second, having a diverse representation of leaders is also critical to convey to staff and students about the different types of successful leaders. As can be seen, this solution pulls together aspects from the previous solutions and demonstrates how structural/cultural support is crucial. If students can see other students that represent them, they are more likely to have self-confidence in their abilities and capabilities. Bigger dojos are more likely to be able to address this issue because of the sheer number of students available as role models. Smaller dojos may struggle with this as there will be less role models available, and thus, potentially less diversity.

Higher ranked students may also struggle with this issue, since there may not be that many students that are higher than them. Although it is possible for lower ranked students to be role models for higher ranked students (I strongly feel this and we actively teach our students this as well), when it comes down to advancing through the ranks, the less higher belts there are

to you, the more likely you could feel like an imposter. There are less physical examples of what your martial arts should look like, or the next higher rank is so much higher than you that their technique is significantly more developed. Thus, you start to question how you could possibly advance any further when the goal posts feel so far away. You also start to question your current ability (why can’t I do that yet? Should I already be able to do that? Perhaps I shouldn’t have my current belt?). For me, I see this as an opportunity to use my role as a senior martial artist to influence the culture for future black belts and help them deal with any imposter feelings they experience.

Conclusion

I started working on this essay at the end of 2019, and it has been a very introspective journey for me. Sometimes I found it incredibly difficult to work on this essay because it can be hard constantly writing about how you feel like an imposter. I definitely have not solved my imposter feelings, but I have learnt different ways to try to address them. I also learnt that a lot of martial artists feel like imposters sometimes, for all sorts of reasons. I think this is an incredibly important area to study, and I hope that in the future I can return to this topic in a professional-capacity and conduct more research so that I can try and help other martial artists like myself.

References

Alvarado, C. (2015). I’m not all that: a look at the imposter phenomenon in intimate relationships. EWU Masters Thesis Collection. http://dc.ewu.edu/theses/277

Beard, J. (1990). Personality correlates of the imposter phenomenon: An exploration in gender differences in critical needs. Unpublished masters thesis, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Borhart, J. (2015). Imposter syndrome: You are not alone. Emergency Medicine News.

Retrieved from: https://journals.lww.com/em-

news/fulltext/2015/06000/News Imposter_Syndrome_You_Are_Not_Alone.3.aspx? casa_token=_FbGUHNlL9IAAAAA:izY1hduKdxjefNxQCzBgCnKnjYT9qFfiN2g6j OH_JquRcB-DFi9q6ZmvPkSc9MqD3bcFWo0i_MiF21EZoxz27cn7Lg

Bothello, J., & Roulet, T. J. (2018). The imposter syndrome, or the mis-representation of self in academic life. Journal of Management Studies, 56, 854-861. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12344

Clance, P. R. (1985). The impostor phenomenon: Overcoming the fear that haunts your success. Peachtree Pub Ltd.

Clance, P. R., & Imes, S. A. (1978). The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: Dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy, 15(3), 241-247. https://doi.org/weblib.lib.umt.edu:8080/10.1037/h0086006

Clark, M., Vardeman, K., & Barba, S. (2014). Perceived inadequacy: A study of the imposter phenomenon among college and research librarians. College & Research Libraries, 75(3), 255-271. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl12-423

Cusack, C. E., Hughes, J. L., & Nuhu, N. (2013). Connecting Gender and Mental Health to Imposter Phenomenon Feelings. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 18(2), 74-81.

Gardner, S. & Holley, K. (2011). “Those invisible barriers are real”: The progression of first- generation students through doctoral education. Equity & Excellence in Education, 44(1), 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2011.529791.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491

Hutchins, H. M., & Rainbolt, H. (2017). What triggers imposter phenomenon among academic faculty? A critical incident study exploring antecedents, coping, and development opportunities. Human Resource Development International, 20, 194- 214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2016.1248205

Jaremka, L. M., Ackerman, J. M., Gawronski, B., Rule, N. O., Sweeny, K., Tropp, L. R., … & Vick, S. B. (2020). Common academic experiences no one talks about: Repeated rejection, impostor syndrome, and burnout. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(3), 519-543. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916198988

Joshi, A. & Mangette, H. (2018). Unmasking of Impostor Syndrome. Journal of Research, Assessment, and Practice in Higher Education, 3(1), 1-8. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/jraphe/vol3/iss1/3

Kamarzarrin, H., Khaledian, M., Shooshtari, M., Yousefi, E., & Ahrami, R. (2013). A study of the relationship between self-esteem and the imposter phenomenon in the physicians of Rasht city. European Journal of Experimental Biology, 3(2), 363-366.

Lacey, S., & Parlette-Stewart, M. (2017). Jumping into the deep: imposter syndrome, defining success and the new librarian. Partnership: The Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 12(1), 1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.21083/partnership.v12i1.3979

Langford, J., & Clance, P. R. (1993). The imposter phenomenon: recent research findings regarding dynamics, personality and family patterns and their implications for treatment. Psychotherapy: theory, research, practice, training, 30(3), 495-501. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.30.3.495

MacInnis, C. C., Nguyen, P., Buliga, E., & Boyce, M. A. (2019). Cross-Socioeconomic Class Friendships Can Exacerbate Imposturous Feelings Among Lower-SES Students.

Journal of College Student Development, 60(5), 595-611. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2019.0056

Mak, K. K., Kleitman, S., & Abbott, M. J. (2019). Impostor phenomenon measurement scales: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00671

Mullangi, S, & Jagsi, R (2019). Imposter syndrome: Treat the cause, not the symptom. A piece of mind. JAMA Net Work, 322(5), 403-404. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.9788

Peteet, B. J., Montgomery, L., & Weekes, J. C. (2015). Predictors of imposter phenomenon among talented ethnic minority undergraduate students. The Journal of Negro Education, 84(2), 175-186.

Sherman, R.O. (2013). Imposter syndrome. American Nurse Today, 8(5), 57-58. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256475007

Sonnak, C., & Towell, T. (2001). The imposter phenomenon in British university students: Relationships between self-esteem, mental health, parental rearing style and socioeconomic status. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 863-874. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00184-7

Tiefenthaler, I. (2018). Conquering imposter syndrome. University of Montana Journal of Early Childhood Scholarship and Innovative Practice, 2(1), 1-3. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/ecsip/vol2/iss1/4

Wang, K. T., Sheveleva, M. S., & Permyakova, T. M. (2019). Imposter syndrome among Russian students: The link between perfectionism and psychological distress.

Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.005

Appendix A – Survey

Information Statement:

Thank you for agreeing to participate in my survey. The aim of this survey is to explore your journey as a martial artist. I hope to recruit people from all backgrounds and all levels.

However, for ethical purposes, you must be 18 years old or older to complete this survey. The survey will take about 15 minutes to complete.

Please be honest in your responses – the results from this survey will be completely anonymous. If there are any questions that you feel might identify you, you can skip them and leave them blank. The results will be discussed in an essay I am developing; however, I will not be mentioning any students by name or pointing out any identifying features (such as belt rank or age).

This survey is not an academic study in the sense that it has not gone through an ethics board. This means that the results from this survey are purely for me to explore in my essay and will not be published anywhere in an academic journal.

In addition, there will be an option at the end to request your responses to be deleted if you wish.

If this survey brings up any uncomfortable feelings, feel free to come and chat to me about them (keep in mind that I am not a trained clinician, but I do love to chat!). You can also contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Please click on the red button below if you are ready to begin the survey.

Demographics:

- Please enter your age (leave this blank if you feel like it might identify you).

- What is your gender?

- Female

- Male

- Other

- What is your belt rank? (leave this blank if you feel like it might identify you)

- White

- One yellow stripe

- Two yellow stripes

- Yellow

- Orange

- Red

- Green

- Blue

- Purple

• Brown 1st Kyu Shodan Ho Shodan Nidan Sandan Yondan Other

- How long have you been on your currentbelt?

- Less than 1 month

- Between 1-2 months

- Between 2-4 months

- Between 4-6 months

- Between 6-12 months

- Between 1-2 years

- Between 2-5 years

- More than 5 years

- What group do you belong to?

- Beginners

- Intermediates

- Advanced

- Black belts

- How many years have you been training in martial arts (including other styles)?

- Have you previously trained in another martialarts?

- Yes

- No

- (IF SELECT YES) Please specify

- Do you currently train in another martial arts (including any of our other programs such as Kobudo, BJJ, Fightfit, etc.)?

- Yes

- No

- (IF SELECT YES) Please specify

- Do you currently do any other sports orexercise?

- Yes

- No

- (IF SELECT YES) Please specify

- On average, how often do train in a week (this can include other training that you might do outside of scheduled classes)?

• 1 day 2 days 3 days 4 days 5 days 6 days 7 days

Enjoyment and Challenge of Karate:

Please rate how much you enjoy the following aspects of karate:

- Fitnesswork

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Stretching and flexibilitywork

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Basics training (punches, blocks, kicks, stepping,etc.)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Kata (i.e., forms such as Kihon DosaIch)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Kumite (i.e.,sparring)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Bunkai (i.e., partner work forms such as the 7 wristescapes)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

• 10 (Really enjoy it)

- Drill work (e.g., real world self-defense, practicing moves from kata as separate drills)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

- Conceptual drills (e.g., more internal or complicated drills such as hipmotion, dead weight,etc.)

| · | 0 (Don’t enjoy at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Really enjoy it) |

Please rate how challenging you find the following aspects of karate:

- Fitnesswork

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Stretching and flexibilitywork

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Basics training (punches, blocks, kicks, stepping,etc.)

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Kata (i.e., forms such as Kihon DosaIch)

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Kumite (i.e.,sparring)

- 0 (Not challenging at all)

- 1

- 2

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Bunkai (i.e., partner work forms such as the 7 wristescapes)

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Drill work (e.g., real world self-defense, practicing moves from kata as separate drills)

| · | 0 (Not challenging at all) |

| · | 1 |

| · | 2 |

| · | 3 |

| · | 4 |

| · | 5 (Neutral) |

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

- Conceptual drills (e.g., more internal or complicated drills such as hipmotion, dead weight,etc.)

- 0 (Not challenging at all)

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5 (Neutral)

| · | 6 |

| · | 7 |

| · | 8 |

| · | 9 |

| · | 10 (Very challenging) |

Imposter Syndrome:

For the following questions, think about your current karate journey and how true these statements are for you:

- I secretly worry that others will find out that I am not as bright and capable as they think I am.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I sometimes shy away from challenges because of nagging self-doubt.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I tend to chalk my accomplishments up to being a “fluke”, “no big deal”, or the fact that people just “like”me.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I hate making a mistake, being less than fully prepared, or not doing things perfectly.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I tend to feel crushed by even constructive criticism, seeing it as evidence of my “ineptness”.

• Not at all true Rarely true Sometimes true Often true Very true

- When I do succeed, I think “Phew, I fooled them this time but I may not be so lucky next time!”

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I believe that other students are smarter and more capable than Iam.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I live in fear of being found out, discovered, or unmasked.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

- I also experience similar feelings as above in other areas of mylife.

- Not at all true

- Rarely true

- Sometimes true

- Often true

- Very true

Debrief Statement and Open-Ended Questions:

Thank you, you are almost there! The survey was actually about the idea of imposter phenomenon (also known as imposter syndrome).

Imposter phenomenon is the persistent inability to believe that one’s success is deserved or has been legitimately achieved as a result of one’s own efforts or skills. This means that people can feel like imposters or frauds even when they are “successful”.

Generally, research focuses on imposter phenomenon in academia. For my essay, I am exploring imposter phenomenon in martial arts. I aim to see if feelings of imposter phenomenon are common across all martial artists, and if there are any common factors between martial artists who experience imposter phenomenon.

For the final questions of the survey, I would like to ask some additional questions about your experiences with imposter syndrome (if any).

- Have you ever experienced feelings of imposter phenomenon throughout your martial arts journey?

- Yes

- No

- How often do you experience symptoms of imposter phenomenon in yourmartial arts journey?

- Not at all

- Rarely

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

- Describe an instance in your martial arts journey where you felt like an imposter. If you have not experienced any feelings of imposter phenomenon, feel free to write “Not applicable”.

- How often do you experience symptoms of imposter phenomenon in other areas of your life (e.g., work, hobbies,etc.)?

- Not at all

- Rarely

- Sometimes

- Often

- Always

Thank you and Consent Item:

Now that you have completed the survey, you have the opportunity to withdraw if you do not wish for me to use your responses. Note that your responses will be anonymous and non- identified within my survey.

- Please indicate whether you want your survey responses to be included in my essay or permanentlydeleted.

- Please INCLUDE my responses. (1)

- Please PERMANENTLY DELETE all of my responses. (2)

If you have any issues or you would like for me to remove your responses at a later date, contact me through Romany.McGuffog@uon.edu.au before the 30th of September 2020. You are also welcome to email me if you would like to provide any additional feedback about imposter phenomenon within a martial arts context.

Appendix B – Graphs for Demographics

Appendix C – Enjoyment and Challenge Levels of Karate Activities