Brian Hayes 2018

What is Koryu?

Generally, koryu means “old school” and generally refers to Japanese and Okinawan martial arts systems that pre-date the Meiji restoration. In the case of Okinawan karate however, the matter is complex. It is worth noting that Okinawan karate was referred, until the 1930’s, as Ti. It was a comprehensive means of self defence, with a strong emphasis on kata, but it could also be transformed into dance, perhaps due to a long history where there was a need for secrecy in training civil self defence methods. The reason for the development of these extraordinary civil self defence methods may be attributed to the 1609 subjugation of Okinawa by the Satsuma of mainland Japan. The Satsuma method of swordplay, Jigen Ryu , can claim to be the koryu tradition introduced to Ryukyu. There is no question that Jigen –Ryu is connected to Okinawa’s domestic fighting tradition however the point still remains, which influenced which? This is interesting, as it presumes that the Okinawan martial arts were imported from Japan. In his book, Kempo Karate, Tsuyoshi Chitose (Chinen Kintyoku) does note that karate was well established at the time of the Satsuma invasion in 1609. He holds the view “. that karate was well established at the time of the Satsuma invasion and that the Okinawans had great confidence in their ability to use karate to defend themselves even then. Therefore, the birth of karate did not occur after the Satsuma invasion. Rather, in my opinion, it is closer to the truth to say that karate actually appeared prior to the period following the reign of King Sho Shin, five hundred years ago.”

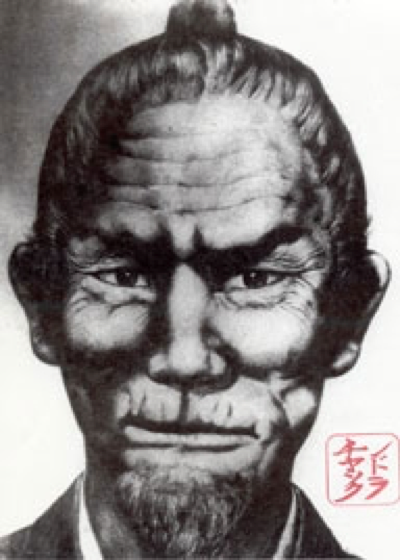

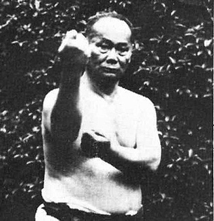

Enter into the historical discussion, Matsumura Sokon ( 1809 – 1899). He was O’Sensei’s grandfather on his maternal side. The title of Pechin was given for his service as the chief martial arts instructor and bodyguard for the last two Okinawan kings, Sho Iku and Sho Tai.

It is interesting to note that Sakumoto sensei has developed a strong rapport with the jigen Ryu style of swordmanship. It was Matsumura who is credited with introducing the principles of Jigen Ryu into Okinawan Kobudo.

Matsumura learned under Tode Sakugawa, who had learned from Kusanku, a Chinese master in Ch’uan Fa. Interestingly, Tode (China hand) was the term used to describe Okinawan martial arts.

Described as blindingly fast and deceptively strong, the tall, thin and intense Matsumura passed on his art to such notables as Itosu Ankoh, Motubu Choyu and his brother Choki, Chotoku Kyan (a teacher of O’Sensei) and Funakoshi Gichin.

Matsumura is credited with passing on the kata Naifanchi, Passai, Seisan, Chinto, Gojushiho, Kusanku and the white crane kata know to Okinawans as Hakkaku.

So what does all this have to do with the concept of Koryu?

Matsumura’s martial arts learning and instruction predates two important crossroads in Japanese and Okinawan history. The first was the Haitorei Edict of 1876 banning the wearing and collection of swords. The second was the forced abdication of the king, Sho Tai, as Okinawa was reorganised as a Japanese prefecture in 1879. This ended centuries of close liaison and tribute to China. If koryu, then means classical, it may be presumed that the kata and techniques of toude developed before the end of the samurai period would be considered koryu, as distinguished from developments in post-samurai Japan. It is interesting to note that the styles developed by Kyan, Motobu, Funakoshi, Miyagi, Chitose and others show considerable variation in technique and emphasis, grouping into two main schools known as Shorei and Shorin. O’Sensei, however, called his book on karate, Kempo Karate-Do, choosing the reference to Chinese roots.

Chito—Ryu kata can be traced to two main teachers, Kyan and Aragaki. The kata Seisan, Bassai (Passai) and Chinto are almost identical to the older versions of Kyan’s kata still extant in Shorin Ryu schools. Kyan’s kata are referred to as koryu, and it may be argued that the Chito-Ryu kata taught in the general curriculum are still “classical” versions. The signature emphasis on two hands (meotode), higher “koryu” style shikodachi and shorter zenkutsudachi (or the absence of it) point to classical Okinawan technique unchanged by the modern emphasis on athletic performance that are evident in modern versions of the same kata, such as Tomari Bassai.

Aragaki taught O’Sensei from the age of 7. He taught Sanchin and possibly Unshu, his version of Sanchin, Sochin, Niseishi and the ceremonial form, Shihohai.

What is unique to Chito-Ryu, however, is the koryu kata demonstrated by O’Sensei to Sakamoto sensei. The kata Tensho, Unsu, Seichin and Hoen are unique and not mentioned or shown in any other style. It is considered they were learned or developed by O’Sensei as components of his Gung Fu no kata, or the embu or moving thesis that demonstrated his deep understandings of kempo. If indeed these kata are components, they are vastly different and each of considerable duration.

Sakamoto sensei wrote in 2004, “There are thousands of variations in karate technique and he expression of kata has infinite variety, because it depends on the individual. That is what I try to feel when I do kata. I mean that kata has a consciousness like a living organism. I truly feel kata has a long history in space and time that has continued its journey. Kata has form but is also formless.”

Classical kata requires a keen sensitivity, a calmness and oneness with nature and a deep knowledge of the principles of karate. To reach towards the koryu level, the practitioner needs to understand the Kei –I concept, where kata are classified in four groups, Moto or preparation kata (Seisan and Niseishi), animal kata (Bassai, Chinto, Rohai, Tenshin, Sochin) and then kata that express human emotion (Sanshiru and Kusanku). Ryushan then bridges to the koryu group that includes Tensho, Unsu and Seichin.

The koryu of Chito-Ryu

O’Sensei wrote, “Our teachers did not give us a clear explanation of the kata from old times. I must find the features and meaning of each form by my own study and effort, repeating the exercises of form through training”.

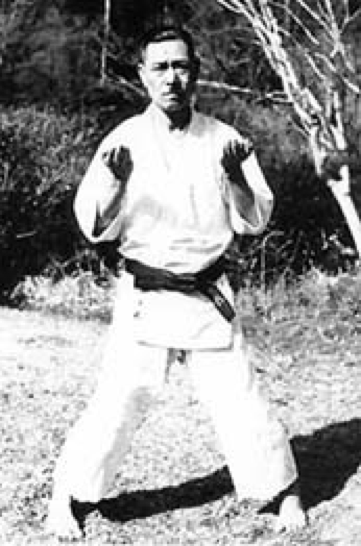

In his book Kempo Karate-do, Chitose sensei listed 32 kata as the kempo kata syllabus, and then added 33 “And others”. This presumes that the list was not definitive. The koryu kata tensho and unsu are mentioned but not Seichin or Hoen, Rochin or Gung fu. These kata were demonstrated to Sakamoto sensei by O’Sensei. Sakamoto sensei believes that these traditions originated in the Southern Shaolin Temple with the Four Gate Fist system. When he first saw Chitose sensei he noted “Hands swirl, drawing mythical circles in the air, ancient dragon dancing”. He said that this meeting with destiny changed the course of his life.

Sakamoto sensei wrote of the legacy of O’Sensei and his koryu kata, particularly the “family” kata Gung Fu. “The majority of Chito-Ryu shihan approach this kata as if it were something sacred or a special Soke kata that is only passed by inheritance to family members. But this is a mistake. My understanding is that a serious karateka who aims to attain true karate can rise to the challenge of this kata. Why did O’Sensei perfom this “secret” form of koryu karate so many times in public, without trying to hide it at all? I think he was trying to say through his techniques, “Look at my moves and my form carefully. See what you can catch. Study more and come up here” (From Ryusei Karate Do: A Personal Perspective, by Peter Giffen.)

The free, independent movements of the hand and its fingers. As Sakamoto writes “Moving freely, hands can mimic the movements of animals such as snakes, birds and monkeys, and like the flow of water in a stream or clouds upon the wind, can repeat the same motion over and over again.”

He writes about Sennhen-bannka-shugi (infinite hand techniques) and maiodoru-te (dancing hands).

Observations of koryu kata

Tensho

Sakamoto sensei writes in The Way of Ten Thousand Day Training Manual, that in Tensho you “Ride the body on the move, put the body and strike it (balance and imbalance). Sanchin yui Tensho is a wonderful kata that can continue training even after having aged.”

Tensho means circling palms, and cannot be attempted until the practitioner has studied the hard and then soft versions of Sanchin for several years. It is a much longer version of the tensho generally known by Goju ryu practitioners, and is practiced in Ryusei karate in tandem with the open handed version of Sanchin. Sakamoto Sensei calls this Sanchin yui Tensho.

It employs such techniques as sashikome, (thrusting?) rasen-te (spiral hand), fumi-sokuto (stepping speed) and madoka (circle).

Unsu

Unsu is “cloud, wind”, and the kata promotes a state of constant movement. Constant practice of this kata promotes a feeling of profound sinking in the lower body as well as delicate and complex kaishu. Stepping in unsu is characterised by nuki stepping, kosa dachi movements in transitions and a constant connection of energy between the fingers and toes.

Sudden transfer of energy into powerful technique is possible, but I feel more a development of flowing technique with a floating feeling that comes from a focus on the tanden and relaxation of the muscles.

Seichin

This kata is difficult to perform, as it is very difficult to define the motion of the monkey. This is itself the attraction. The monkey motion is at times extremely quick, showing greedy, thoughtless and even ill discipline behaviour as well as delicate and tactile movements. There can also be heavy slapping, tearing, grappling, pinching, dislocating technique.

Posture in seichin indicates a particular emphasis on hakamagoshi. I have found that in adjusting posture to use hakamagoshi, there is a great awareness of the energy coming from the ground through the base of the spine. the chin thrusts forward slightly and the eyes are more intense. It is my view that hakamagoshi induces a greater intensity and is most suited to the dangerous and volatile emotion of the monkey, which vacillates very quickly between nurture and cruelty.

A particular consequence of Seichin practice is the change in henshuho technique. Many of the henshuho techniques become much clearer after studying the shifting, grabbing, sudden height change and double open hand techniques that the kata prompts.

Principles of Koryu Training

In the regular practice of Sanchin through to Seichin I have tried to be mindful of the following principles and to cultivate them separately and together, as they work in concert to develop a sounder technique.

Ishikiis consciousness, but in a martial arts context it is much more. It is an elevation of consciousness into the heightened state of arousal similar but not the same as that usually induced by the swelling of the amygdala promoting the release of cortisol and adrenaline and that state often called the fight or flight response. The problem with the fight/flight response is that it can’t be maintained for long and one could not live comfortably in an environment where constant amygdala arousal, or a fear response occurs. Instead, the martial artist elevates their sense of acuity, or environmental awareness, peripheral vision and acute body awareness and balance.

Ishiki requires intense introspection in accord with the physical requirements of the situation. Just as tenchin no kamae is a physical connection of earth, sky and the person between, it is must also be balanced with mental awareness.

Practice of Sanchin, particularly sanchin yui tensho, promotes this feeling by broadening the perspective, promoting awareness of both mae and ushiro tanden and a feeling of connection of ue and shita tanden through the naka tanden (solar plexus). Ishiki requires, then, a balance and intense awareness of the physical and mental self in its environment. The concept of enzan no metsuke, then, becomes too simple, as the kamae required is 360 degrees outwards as well as an acute awareness of self.

Itosu, quoted in Chitose Sensei’s book Kempo Karate Do, seemed to be describing cultivation of Ishiki when he wrote his Principle no 8, “When practicing karate, your eyes should glare with the feeling of actually going out onto the battlefield. The shoulders should be down and the body hardened, and you should have a feeling of actually blocking an opponent and actually striking an opponent right there in front of you… If you constantly practice this way, these skills will spontaneously appear on the battlefield.” More than this, though, is the ability not just to perceive the enemy with great intensity, but to see everything. Ultimately, then, the practice of kata promotes an awareness of nature, and the interaction between one’s own energy and that of the natural world.

Muchimimeans to be sticky and heavy, like mocha, the sticky, glutinous rice ball that is well known in Japan and Okinawa. It is muchimi that really distinguishes koryu kata performance from modern athletic performance. The modern performance places an emphasis on correct form, explosive power, athletic performance and visual beauty of the kata. Koryu kata, however, can appear to be slower, as though the practitioner is constantly engaged with an invisible foe. At long range, technique can appear heavy and increase in speed toward the target. The power comes from the relaxation of weight, sinking of the tanden, and correct use of breathing and hips. At close range, muchimi is most important in maintaining connection with the opponent with a heavy, sticky feeling. Kake uke, for example can be applied and the opponent’s energy redirected without the need to actually hold. This also true of osae techiques, where the combination of sinking (shizume) and muchimi allow control of the opponent. Basically, muchimi is he ability to use body elasticity to balance the flexor and extensor muscles in an explosive release, a co-concentric contraction if you would. In Ryusei karate method, however, this type of sticky and sinking technique is referred to as Nebari, which means to stick.

A second kanji for the word muchimi means whipping power. This is particular to Shorin Ryu technique and, like whipping a wet towel, requires minimal tension to accentuate the energy delivery from the hip turn and sudden retraction (shimegoshi).

The ultimate aim of both methods is the development of hakkei. The challenge is to decide which technique to employ. Generally, it may be said that Naha te uses muchimi ( or better referred to as Nebari) for development of power at close range, using neri and shibori as important ingredients in this. Shuri te, is often described as more suited to longer range technique. The whipping motion is certainly accentuated if the limb is able to be extended fully. One would think that a good knowledge of both distances is essential to a more complete understanding of karate.

Shimegoshi/ Hakamogoshi

The diagram made by Sakamoto sensei amply demonstrates the concept of Shimegoshi, and is much clearer than a lengthy written description could offer. The awareness of shimegoshi has become clearer with the introduction of Naihanchi kata, and this has meant a re-assessment of the ways in which we generate power in Chitokai karate. Previously, there was an assumption that neri, hari and shiburi were the prime ingredients, but Naihanchi re-introduces the Shuri component passed on through Kyan Chotoku and others. Sakamoto’s sensei’s dialogue with Shinzato sensei in Okinawa has prompted his close attention to the importance of Shimegoshi, along with hakamagoshi.

Chinkuchi

Higaonna Morio describes chinkuchi as “the tension or stability of the joints in the body for a firm stance, a powerful punch or a strong block. For example, when punching, or blocking, the joints of the body are momentarily locked for an instant and concentration is focused on the point of contact….. thus a free flowing movement is suddenly checked for an instant, on striking or blocking, as power is transferred or absorbed.” Again, the role of hip retraction (shimegoshi) is important here.

Meotodewas clearly explained by Choki Motubu. “Me-oto-de is a principle of karate that must be adhered to at all times. Even in everyday life for example, when pouring alcohol, holding a cup, or picking up chopsticks – students of kempo must follow this principle so as to make it a part of themselves.”

What he meant was that the left and right arms need to be utilized tin concert. The term can be translated as “husband and wife hands”.

Sakamoto sensei has often said that we must consider the other hand at all times. Certainly, it is fundamental to koryu kata to employ both hands in technique, and even more importantly, to use each hand to block and attack at the same time. Niseishi teaches us clearly the importance of morote, or of using both hands to support each other and also to deliver simultaneous defence and attack. The opening move in bassai is also a clear example of this. It also explains why some of the techniques in koryu kata appear to be less powerful than “modern” kata due to the emphasis on the block turning into a strike. So sinking, shimegoshi and spiral hands make perfect sense when we consider me—oto-de.

Motobu also said “A defending arm must always be able to transform to an attacking arm. Defending with one arm and attacking with the other is not true bujutsu. Achieved with further development, the waza of defending and attacking at the same time is true bujutsu.”

Doin

Cultivation of ki is an important process in the search for koryu understanding. As a beginning point, the kata shime no kata, niseishi and sanchin will encourage development of ki in the context of karate training, rather than as an independent study. It is my view that while doin exercises are useful in developing some feelings of energy flow, and standing meditation is also valuable, time is best utilized in the practice of sanchin both in its hard and soft presentations. After many years of hard sanchin practice developing timings from 4 seconds, then to 7 then to 10 seconds per contraction, or breath, I have found that open handed sanchin profoundly develops internal awareness, connection with the environment and various feelings of sinking and floating that I feel are necessary to step into the koryu kata world.

Interestingly, one morning my training partner, Ashley, and I chose to perform Sanchin Yui tensho on the waters edge. The feelings of ki flow in the body when facing first the water and then the thick vegetation behind were decidedly different and we found also a difference in elevated awareness of surroundings and enhanced peripheral vision. This relates to earlier description of the importance of development of Ishiki.

Conclusions

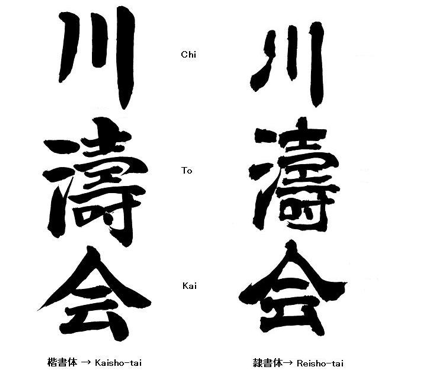

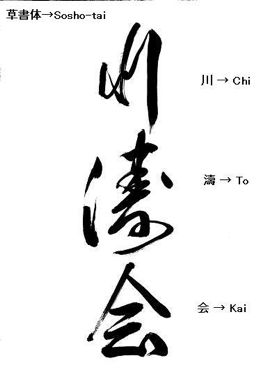

There is much to humble and uncertain about when facing the study of koryu kata. Sakamoto sensei has often said the O’Sensei has challenged us to climb the wall that separates us from the koryu world, but with little but one’s own instincts and rare visual example from sensei, it is an uncertain venture. For myself, the more I read and practice, the more I see the enormous physical and mental complexities of the classical tradition. An image that carries me is one I saw when Sakamoto sensei drew for me the three styles of our Chito-Ryu name. We had decided to re-name our style as I did not want to carry the same characters as those of the ryu inherited by the son of Chitose sensei. He explained the styles were Kaisho, Reishi and Sosho, and they were a sound lesson and related to the other better known concept, Shu Ha Ri.

A study of the Kei-I kata begins in Kaisho method, where the characters are clear, and like the brush lifting from the page, the practitioner seeks to develop strong and precise kihon.

The next level is Reisho, where the brush may lift between characters, but at other times the stroke order runs together. This is mastery of the kata program, and the style is clear and recognisable, although allowing some interpretative difference.

The koryu world, however is sosho. Here the calligraphy is stylised, and the characters may not even be recognisable except by another expert. Characters run together as the pen does not lift from the page, and some parts may even be shortened or left out in the interest of the overall emotion and interpretation of the artist. If this is koryu kata, then it explains clearly why it cannot be taught, but must be practiced and pained over for many years in lonely physical and introspective pursuit.

Peter Giffen wrote once that he saw O’Sensei, just before his death, practicing some sequence he had learned, perhaps 60 years before, and was still not satisfied with. I note that Sakamoto sensei, after producing instructional manuals and writing and demonstrating exhaustively, recently introduced his Way of Ten Thousand Day training manual. He is driven with enormous energy to pursue the teachings of Chitose Sensei and to pass on the traditions to others. In that sense, then, and paradoxically, the student who seeks to understand the koryu tradition, will probably never know when and if they ever arrive.